Lanza’s dream of turning human embryonic stem cells into therapies for the sick and the suffering is taking a huge step closer to reality.

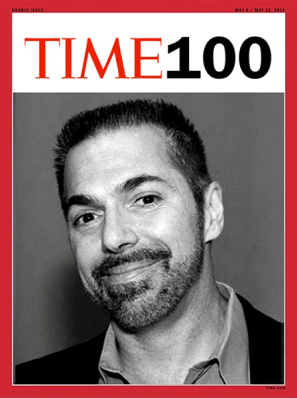

May 23 & 30, 2011

Stem cells from embryos may finally cure patients—reviving a bitter debate.

By Sharon Begley

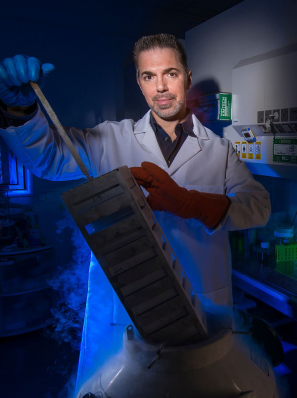

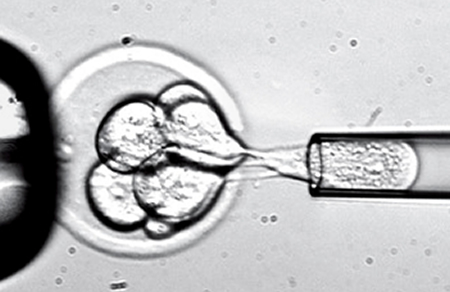

Stem cells are taken from donated human embryos, then grown in a lab until they differentiate into cells that can treat macular degeneration.

Stem cells, it seems, have become almost as ubiquitous in medicine as stethoscopes. Yankees pitcher Bartolo Colon received injections of stem cells from his own fat and bone marrow to treat an injured shoulder and elbow, his doctor recently revealed. Meanwhile, a Texas hospital is testing whether stem cells from a patient’s bone marrow will improve the effectiveness of cardiac bypass surgery. It’s enough to suggest that the bitter religious, ethical, and political battles over stem cells that began in 1998 were pointless. If cells harvested from patients themselves can treat disease, perhaps there’s no need to use ones obtained from human embryos—with all the questions that raises.

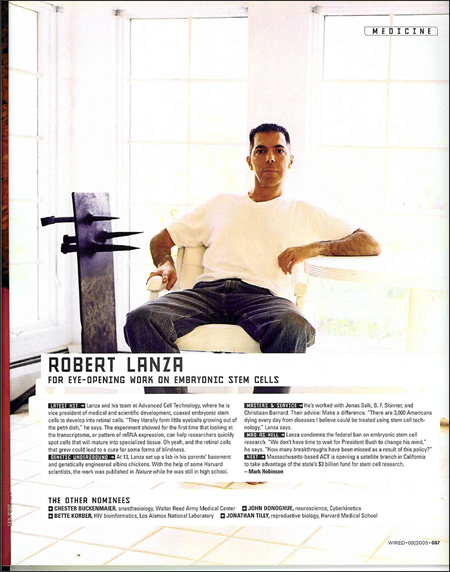

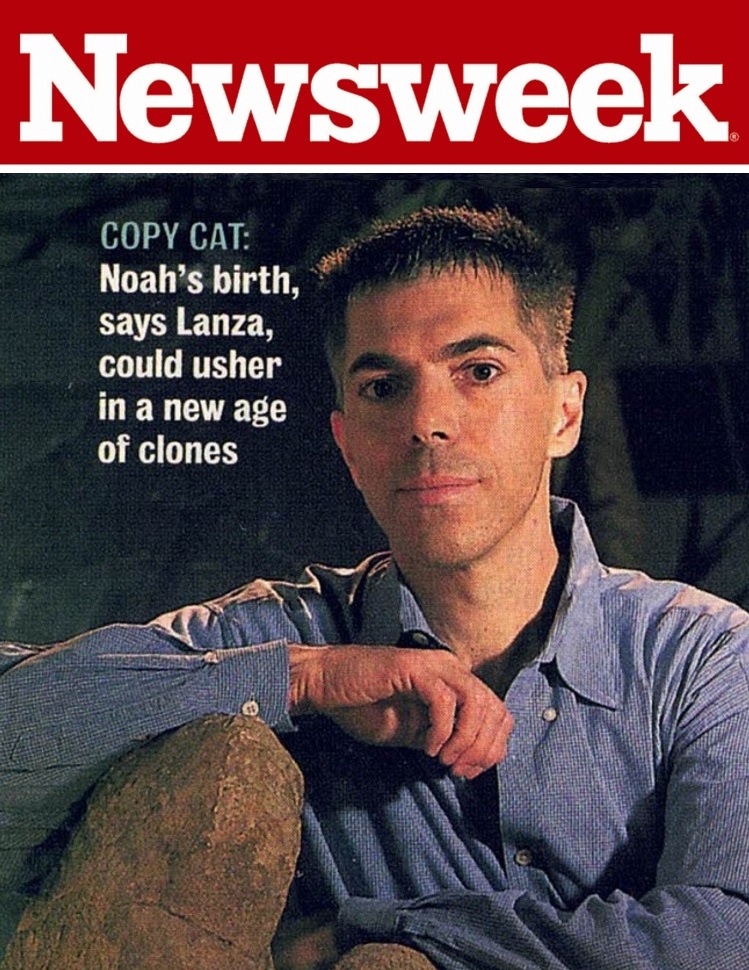

To Robert Lanza, this argument is just another in a long line of attacks that have come at him nonstop for 10 years. As chief medical officer of Advanced Cell Technology, a leading stem-cell company, he has no doubt that adult stem cells will fall woefully short of the promise of embryonic ones. “Adult stem cells can’t do all the same tricks,” he argues. “There are over 3,000 Americans who die every day from diseases that could be treated with embryonic stem-cell therapies.” His single-minded determination has made him a punching bag for U.S. senators, the Catholic Church, and his fellow stem-cell scientists, to name but a few who have attacked his research. “The Catholic Church might just as well have put a price on my head,” says Lanza, himself a born and confirmed Catholic. Advanced Cell was bombarded with scathing emails accusing its scientists of having perverted sex in the labs and ripping limbs off babies, with some so threatening that a Massachusetts judge issued a subpoena to trace the senders.

But vindication may be near. Lanza’s dream of turning human embryonic stem cells into therapies for the sick and the suffering is taking a huge step closer to reality. As early as next month, the first patient will undergo a revolutionary procedure aimed at restoring sight. A bioethics board at UCLA recently approved a clinical trial of cells Lanza has produced from human embryonic stem cells—obtained from donated in vitro fertilization embryos—to treat blindness. If all goes well, it will be the first study to show whether human embryonic stem cells can cure disease.

It’s already bringing ethical questions front and center. After Lanza approached ophthalmic surgeon Steven Schwartz of UCLA about leading the clinical trial, Schwartz consulted two patients he considers “religious authorities”: elderly nuns who were losing their eyesight to macular degeneration, which affects about 17 million Americans and is the most common cause of blindness in people over 60. Schwartz told the nuns the trial would use cells from human embryos. “I asked, would that keep you from being in the trial? I got the same response from both: if God gave people the capacity to do this cutting-edge science, then we should.”

To Lanza, the irony was almost painful. As soon as James Thompson of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, announced in 1998 that he had taken days-old human embryos and derived stem cells—which give rise to every kind of cell and thus hold out the promise of curing diseases from Parkinson’s to juvenile diabetes—the science has been both besieged and stymied by religious and moral objections. Taking stem cells from days-old embryos usually destroys the embryo; to Catholics and others who believe life begins at conception, that is murder. After President Bush banned the use of federal money for most embryonic-stem-cell research in 2001, it was left to private companies (or academic labs using private money) to carry the ball.

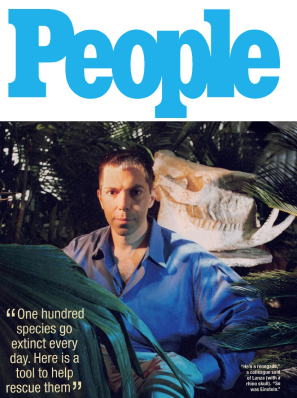

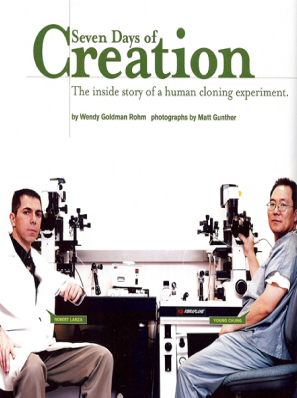

Advanced Cell saw an opportunity to pioneer treatments. Lanza’s team had already gained fame for cloning a wild ox from cells belonging to one that had died in the San Diego Zoo a quarter century before—a tiny step toward a real-life Jurassic Park. But financially, the company was struggling. It faced multiple near bankruptcies from 2002 to 2004, when the CEO managed to talk actor John Cusack and novelist Robin Cook (Coma) into making investments in order to stay afloat.

In 2004, Lanza and colleagues published a paper showing that they could coax stem cells from human embryos to become retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, which lie at the back of the eye and nourish the retina’s rods and cones with “trophic” (growth) factors. When RPE cells die, as they do in macular degeneration, the photoreceptors begin to die, too, and the patient goes blind. Transplanting RPE cells grown from stem cells might rejuvenate the eye’s rods and cones, restoring lost vision.

One summer morning, Lanza arrived at work to find a police officer waiting for him. The cop had read a newspaper story about Lanza, and had a teenage son who was slowly going blind from a degenerative eye disease. Might your cells help my boy? he asked.

Lanza sighed. Advanced Cell didn’t have the $20,000 needed for those experiments. I can’t help your son, Lanza said, but I promise to do everything in my power to get the project moving again.

Advanced Cell sold shares to the public in 2005, and suddenly had funds for Lanza to do the key experiment: he transplanted his RPE cells into mice with retinal disease. Untreated mice went blind. But in mice given RPE cells, the photoreceptors came roaring back, rescuing the animals’ vision. Unfortunately, in 2008, Advanced Cell’s stock price collapsed to a penny, and it laid off everyone but Lanza and four others.

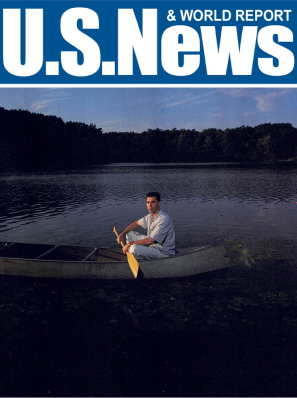

In his quest to prove the value of stem-cell treatments, researcher Robert Lanza has overcome powerful foes and the near bankruptcy of his company.

A new CEO got the company back on its feet financially, and in January the Food and Drug Administration approved its request to run an RPE-cell clinical trial to treat macular degeneration. Along with a clinical trial for a related vision disease, Stargardt’s, the trials will cost Advanced Cell $5 million to $7 million, says CEO Gary Rabin: “For the first time in the company’s history we can afford to pay for clinical trials.” They will not be the first clinical trials using cells made from human embryonic stem cells. That feat belongs to Geron Corp., which last year launched a trial focusing on spinal-cord injuries. But only one patient has been treated, and it will take months if not years to know if the treatment helped.

The Advanced Cell study should therefore be the first-embryonic-stem-cell trial to get results. When that first patient arrives at UCLA for treatment, Schwartz will use a delicate cannula to transplant some 50,000 retinal epithelial cells into the back of the patient’s eye. If all goes well, he will treat 11 more patients. It should be clear this summer if the therapy is restoring vision.

But not for Schwartz’s two nuns. Tragedy struck one earlier this month, when she was diagnosed with cancer that will keep her out of the trial. As for the other sister, despite her previous assent, she decided to seek pastoral counseling. The sister, who asked that she not be named so as not to anger Church authorities, says she concluded that “the destruction of embryos [to obtain stem cells] is a gravely immoral act.” As she goes blind, she says, she is “praying to the Holy Spirit that scientists discover how to use adult stem cells” to treat her disease.